The Einstein You Didn’t Know

1921 Nobel Prize in Physics Revisited

This article is far from the first on Einstein and surely won’t be the last one either.

But I assure you, there is a reason why you need to read this one as well. Most know the man with uncombable hair for his elegant E = mc²; few for his work on ‘warping of the fabric of cosmos’ and others still for his interesting worldview. However, like any ‘academic socialite’, Einstein’s celebrity status overshadowed his other major achievements, especially the one which got him the Nobel Prize. So, that is what we will talk about today.

In 1921, Albert Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect”.

A Problem for Planck

Planck’s remarkable theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1918, suffered from a variety of drawbacks and seemed to lead to a dead end.

While addressing his fellow community members when he was receiving the Novel Prize, Planck himself recognized, “But even if the radiation formula proved to be perfectly correct, it would after all have been only an interpolation formula found by lucky guess-work and thus would have left us rather unsatisfied. I therefore strived from the day of its discovery, to give it a real physical interpretation and this led me to consider the relations between entropy and probability according to Boltzmann’s ideas. After some weeks of the most intense work of my life, light began to appear to me and unexpected views revealed themselves in the distance.”

He originally regarded the hypothesis of dividing energy into increments as a mathematical ‘trick’ introduced merely to get the correct answer. Given such a heuristic argument was an integral part of his derivation, more was needed than just an ‘accidental’ agreement with the experiments to the justify the same.

So, the story of Planck’s rise to stature was quite intertwined with that of others, such as Einstein who built upon his work, guided by Planck’s ‘insight’ of quantization.

But before we learn about Einstein’s work on the same, we must review Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism and what it revealed to us about the nature of light.

Let there be Light…

Light has been the subject of intense probing for millennia.

We have come a long way from Plato’s theory of vision in which light consisted of rays emitted by the eyes whose striking on the object allowed the viewer to perceive things such as the color, shape, and size of the object.

Though we will be adressing the history of light and its physics in a separate article, the key takeaway is that 2 competing behaviours of light kept physicists scratching their heads for quite a few centuries. These were namely the particle nature and the wave nature of light. For instance, the photoelectric effect that will be discussed in detail later on is a demonstration of light’s particulate nature while Young’s Double Slit Experiment is that of its wave nature.

Young’s Double Slit Experiment shows wave nature of light

(Source : https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/114926/youngs-double-slit-experiment-what-would-happen-if-the-first-slit-was-too-w)

Interestingly, when Maxwell arrived on the scene though, his goal wasn’t to understand light.

The Scottish genius was trying to create a framework to explain the properties of electricity and magnetism which had already been studied extensively by the likes of Oersted, Ampere and Faraday.

Maxwell & Electromagnetic Light

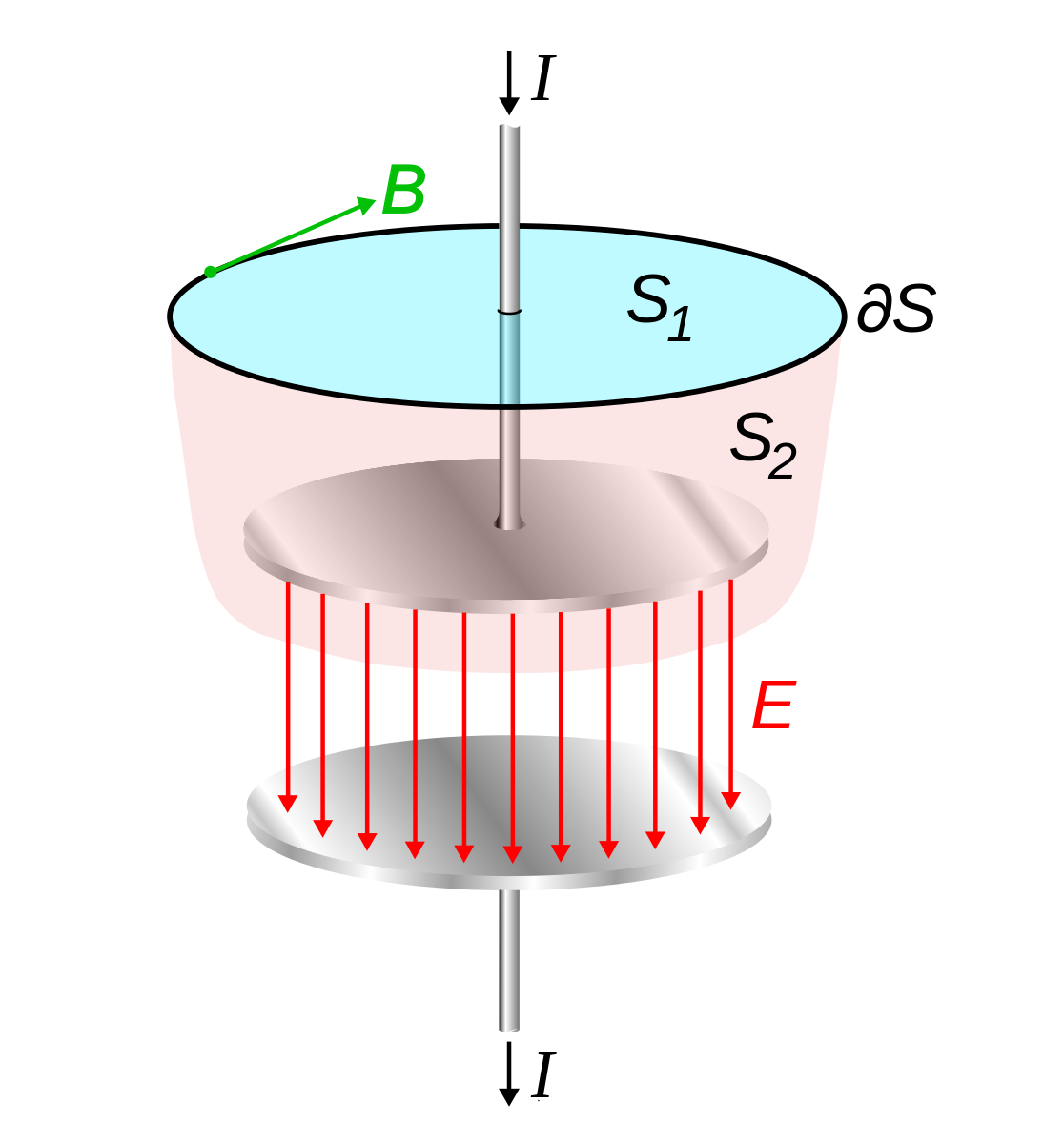

During this time, Maxwell made a correction to Ampère’s Circuital Law (now known as Ampère-Maxwell Equation after the correction).

This was done in order to properly describe current flowing through an electric capacitor. On paper, the correction corresponds to the addition of just a small term of ‘displacement current’ to the last of 4 laws that he formulated with his English comrade Oliver Heavyside. But it is this very term that revolutionised the way we think about light.

Displacement Current flowing through a capacitor

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Displacement_current_in_capacitor.svg)

The previous laws told us about the existence of the electric and magnetic fields along with the creation of former via changing flux of the latter. The extension of the 4th law resolved this asymmetry of interdependence, thus implying that changing electric fields could in fact create magnetic ones. What that means is, if a distrubance is created in either of the fields, it is carried over through space like a wave. These waves are produced in the ‘electromagnetic field’ itself and math showed that these must travel at a constant speed. Coincidentally, the speed came out to be nearly 3×10⁸ m/s, which is exactly the speed of light. Hence, Maxwell had shown that light was an electromagnetic wave.

And important consequence of this electromagnetic wave idea is the realisation that different wavelengths of light appear to us as different colours. But more importantly, it enlightened us of a whole spectrum of invisible waves, of which the light visible to us constitutes only a small part. Unfortunately, Maxwell could not see the fruits his insights had brought.

It was only in 1888, 9 years years after Maxwell’s death, German physicist Heinrich Rudolph Hertz discovered radio waves which finally confirmed Maxwell’s theory by proving that invisible electromagnetic waves exist.

On the Photoelectric Effect

Planck thought of his concept of quanta as nothing more than a mathematical tool to get the theory to match experiment.

Einstein on the other hand, considered it a fundamental phenomenon. For him, light and the electromagnetic field itself, was quantized. Planck had assumed that just the vibrations of the atoms were quantized and had thus quantized the energy of the oscillators forming the walls of his version of the blackbody.

Einstein, however, wondered if Maxwell’s description was compatible with Planck’s blackbody formula.

Einstein’s paper

In his 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect, Einstein wrote,

‘Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetic processes in so-called empty space differs in a profound, essential way from the current theoretical models of gases and other matter. On the one hand, we consider the state of a material body to be determined completely by the positions and velocities of a finite number of atoms and electrons, albeit a very large number. By contrast, the electromagnetic state of a region of space is described by continuous functions and, hence, cannot be determined exactly by any finite number of variables.

Thus, according to Maxwell’s theory, the energy of purely electromagnetic phenomena (such as light) should be represented by a continuous function of space. By contrast, the energy of a material body should be represented by a discrete sum over the atoms and electrons; hence, the energy of a material body cannot be divided into arbitrarily many, arbitrarily small components. However, according to Maxwell’s theory (or, indeed, any wave theory), the energy of a light wave emitted from a point source is distributed continuously over an ever larger volume.’

He adds that, ‘The wave theory of light with its continuous spatial functions has proven to be an excellent model of purely optical phenomena and presumably will never be replaced by another theory. Nevertheless, weshould consider that optical experiments observe only time-averaged values, rather than instantaneousvalues. Hence, despite the perfect agreement of Maxwell’s theory with experiment, the use of continuous spatial functions to describe light may lead to contradictions with experiments, especially when applied to the generation and transformation of light.

In particular, black body radiation, photoluminescence, generation of cathode rays from ultraviolet light and other phenomena associated with the generation and transformation of light seem bettermodeled by assuming that the energy of light is distributed discontinuously in space. According to this picture, the energy of a light wave emitted from a point source is not spread continuously overever larger volumes, but consists of a finite number of energy quanta that are spatially localized at points of space, move without dividing and are absorbed or generated only as a whole.’

Einstein described light as a beam of particles whose energies are related to their frequencies according to Planck’s formula. When that beam is directed at a metal, the photons collide with the atoms. If a photon’s frequency is sufficient to knock off an electron, the collision produces the photoelectric effect.

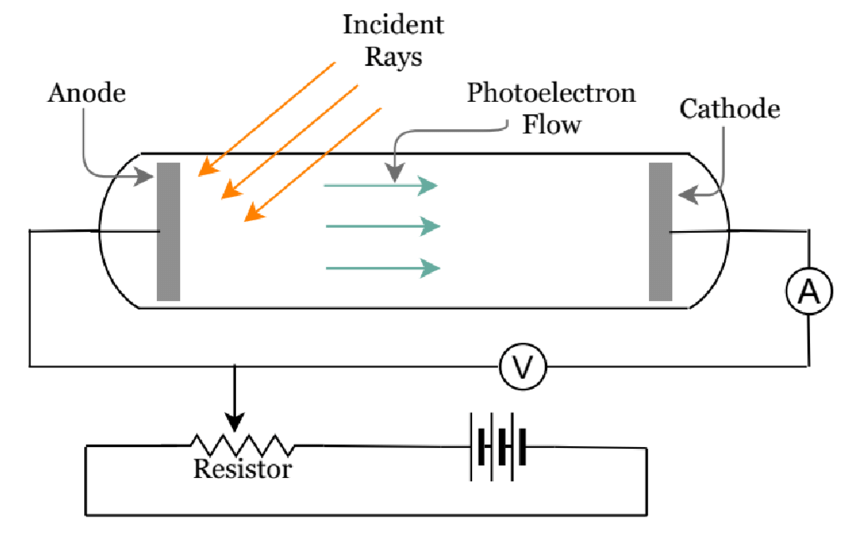

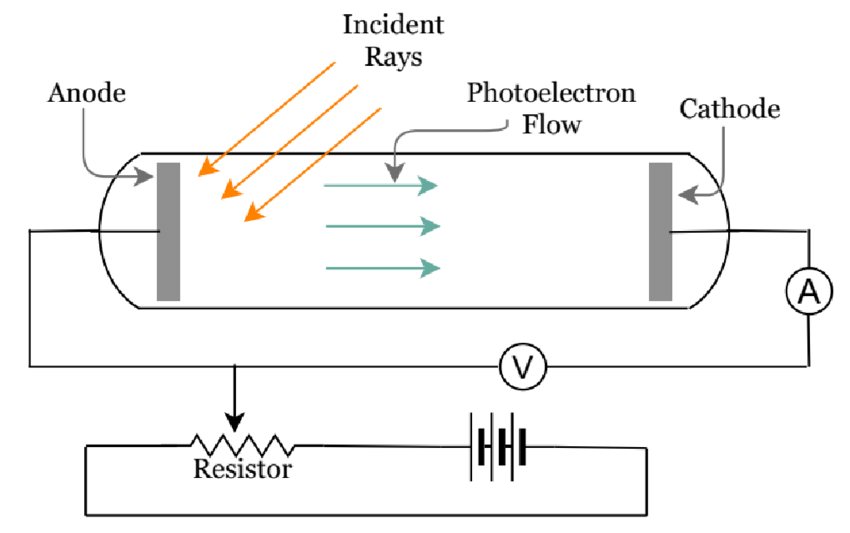

Schematic diagram of Photoelectric effect setup

(Source : A Set of Virtual Experiments of Fluids, Waves, Thermodynamics, Optics, and Modern Physics for Virtual Teaching of Introductory Physics by Neel Haldolaarachchige and Kalani Hettiarachchilage)

As a particle, light carries energy proportional to the frequency of the wave; as a wave it has a frequency determined by the particle’s energy. Hence, Einstein concluded that each wave of frequency f must be associated with a collection of photons with energy hf each, where h is Planck’s constant. He suggested that this idea would explain certain experimental results, most notably the photoelectric effect.

Hostile Reception of Light Quanta

The idea was, however, ill-received.

Not as much because of its novelty as much due to its contention with the most well-established theory on the wave-nature of light in existence, that of Maxwell’s.

The concept of light quanta faced hostility and was unequivocally rejected by all leading physicists of the time, including Niels Bohr and Max Planck himself.

Only when Robert Millikan conducted detailed experiments on the photoelectric effect in 1919, and the measurement of Compton scattering were presented, did the it catch attention of the community. The attempts to reconcile quantization with light propagation phenomena were met with numerous obstacles.

Being a visionary, Einstein recognized their fundamental character and never stopped tackling them until they were solved, partly by himself and partly by others.

Significance

Einstein’s work on the theory of light, to say the least, revolutionised physics.

It not only resovled the strange case of photoelectric effect, but also bridged the gap in Planck’s understanding of his own creation, establishing quantization as an inherently foundational principle in physics which later led to advancements the theory of wave-particle duality in quantum mechanics.

Arrhenius expressed his admiration for Einstein’s work and noted, ‘Owing to these studies by Einstein the quantum theory has been perfected to a high degree and an extensive literature grew up in this field whereby the extraordinary value of this theory was proved. Einstein’s law has become the basis of quantitative photo-chemistry in the same way as Faraday’s law is the basis of electro-chemistry’.

The phenomenon is studied in numerous areas of research, for instance in condensed matter physics, solid state, and quantum chemistry to draw inferences about the properties of atoms, molecules and solids.

The effect has found use in devices specialized for light detection and precisely timed electron emission such as photomultipliers and photoelectron spectroscopy.

On Brownian Motion

Even after such a long, drawn out discussion of his work on the photoelectric effect, we have managed to cover only one of the 4 miraculous papers of the former patent clerk.

We now come to the other often overlooked achievement of Einstein, his work on Brownian Motion.

Einstein was developing his own form of statistical mechanics - a ‘general molecular theory of heat’, for which he used mechanics, atoms and statistical arguments. This statistical molecular theory of liquids was used by him for his doctoral dissertation at the University of Zurich. He had applied the molecular theory of heat to liquids to explain the puzzle of so-called “Brownian motion” as well.

In 1827, the Scottish botanist Robert Brown noticed that pollen grains suspended in water moved in an irregular and random motion. This motion, called Brownian motion, is due to the impact of the molecules of the fluid surrounding the object.

Pollen grains suspended in water

(Source : https://uvachemistry.files.wordpress.com/2020/12/v11qmz.gif)

It took Einstein’s genius to draw parallels between this odd phenomenon and the supposed existence of atoms and molecules. He thought that if tiny but visible particles were suspended in a liquid, the invisible atoms in the liquid could cause the random motions of these particles by colliding with them. A large number of such miniscule collisions with these alleged invisibles could mimic the observation.

Einstein went on to explain the motion in detail, accurately predicting the irregular, random motions of the particles, which could be directly observed under a microscope. Presenting a theory of Brownian motion based on the kinetic theory of gases, Einstein gave a new and direct method for determining Boltzmann’s constant and thus Avogadro’s number. This reasoning also amounted to almost a ‘proof’ of the existence of molecules.

By May 1908, Einstein had published a second paper on Brownian motion providing even more detail than his 1905 paper, and suggesting a way to test his theory experimentally. The problem of the verification of this theory was taken up by the 2 future Nobel Laureates - Jean Baptiste Perrin and Theodor Svedberg.

That same year, Perrin conducted a series of experiments on Brownian motion that confirmed Einstein’s predictions. Perrin wrote that his results “cannot leave any doubt of the rigorous exactitude of the formula proposed by Einstein”.

His work on the same and the discovery of sedimentation equilibrium earned him his own Nobel Prize in Physics, in 1926.

Relativity

There’s lots to talk about when it comes to Einstein, especially about the year 1905.

But I will deliberately treat the section on relativity with a stingy hand, if not an iron fist. This brevity stems from the inability of such a short article to explain, with eloquence, the ramifications of the idea.

I may as well write a separate article entirely dedicated to the development of the theory of relativity.

With his paper, ‘On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies’, Einstein sought to resolve the conflicts between Maxwell’s equations and the laws of Newtonian mechanics by introducing changes to the laws of mechanics. The effects of the changes were to be significant only at considerable fractions of the speed of light.

The theory developed in this paper later became known as Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity. What followed was his work on Mass-Energy Equivalence, a consequence of his work on Special Relativity, commonly known by E=mc².

This work too invited many skeptics, but unlike his light quanta, the elegant equation did succeed in capturing the attention of one man in particular; none other than Max Planck.

Conclusion

Through his legendary ability to peer into the inner workings of fundamental phenomenon, Einstein revolutionsed physics is not one but several distinct and equally important ways.

So much so that he became a household name, a synonym for ‘genius’, and an inspiration for students like you, I and thousands of young physicists around the world and will continue to serve as the same for generations to come.

References

- On a Heuristic Point of View about the Creation and Conversion of Light (1905) by Albert Einstein (Annalen der Physik 17)

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1921/ceremony-speech/

- https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200501/history.cfm

- https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200502/history.cfm

- https://www.iop.org/explore-physics/big-ideas-physics/maxwells-equations#gref